In this article, we will analyze the behind the neck pulldown, an exercise that has been much debated in recent years due to its high risk of injury.

What is the behind-the-neck pulldown?

The behind-the-neck pulldown is a pulling exercise performed on the weight machine, targeting the latissimus dorsi, teres major, and rhomboid muscles (9).

The biceps brachii, lower trapezius, and brachioradialis also play a role in the movement (9).

For beginners, high pulley pulldowns are very useful as they allow for the gradual acquisition of strength to progress to fixed bar pull-ups (pull-ups) (9).

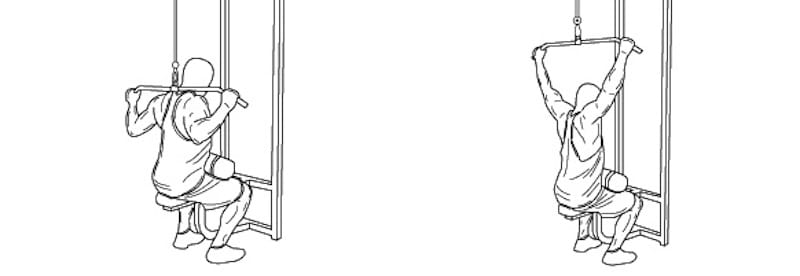

How to perform the behind the neck pulldown?

In the following section, we briefly explain how to perform this exercise.

Starting position

Seated facing the machine, thighs secured under the pads, bar gripped with a pronated grip, and hands spaced wider than shoulder-width apart (3).

Execution phase

- Inhale and pull the bar to the nape of the neck, directing the elbows towards the torso (3).

- Exhale at the end of the movement (3).

What is worked in the behind-the-neck pulldown?

The primary focus is on the latissimus dorsi, responsible for the pull. However, a large number of synergistic muscles are also activated: Biceps, Rhomboid, Infraspinatus, Levator scapulae, Posterior deltoid, Triceps, and Pectoralis minor.

However, we must consider that it is a harmful movement for our shoulder joint.

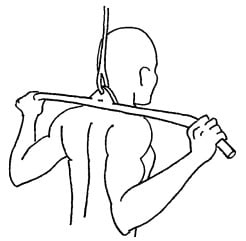

The movement the shoulder makes in the behind-the-neck pulldown is horizontal abduction combined with external rotation.

Numerous scientific studies have concluded that this movement can be detrimental to our glenohumeral joint.

Carpenter et al. (2007) compared muscle activation between the behind-the-neck pulldown and the front pulldown and found no significant differences except in trapezius activation, which was greater in the behind-the-neck pulldown.

The movement the shoulder makes in the behind-the-neck pulldown is horizontal abduction combined with external rotation.

Numerous studies have shown that this movement is very harmful to the glenohumeral joint.

En este curso vamos a tratar el entrenamiento de la fuerza orientada a la hipertrofia muscular, buscando las formas de optimizar el proceso a la hora de planificar las cargas y las sesiones de entrenamiento.

Aprenderemos a determinar cuándo nos interesa conseguir esa hipertrofia, cómo esta afecta a los niveles de fuerza y la importancia de conocer el estado inicial de la persona que se someta a este tipo de entrenamiento.

Analysis of a scientific study

In a study by Sperandei et al. (2009), 24 trained adults performed 5 repetitions at 80% of 1-RM of the behind-the-neck pulldown, the front pulldown, and the V-bar pulldown.

The authors observed muscle activation of the pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, posterior deltoid and biceps brachii in each of the exercises to see their differences and similarities.

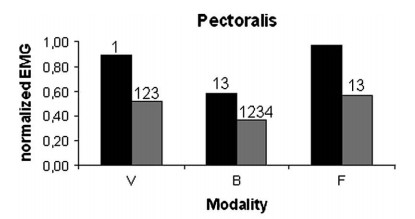

Muscle activation of the pectoralis major

Below we see the muscle activation of the pectoralis major in the concentric and eccentric phases of the behind-the-neck pulldown.

Black bar = concentric phase / Gray bar = eccentric phase

In the concentric phase of the exercise, the pectoralis major showed a higher percentage of activation in the front pulldown, followed by the pulldown performed with the V-bar (9).

The exercise where the pectoralis major was least activated in the concentric phase was the behind-the-neck pulldown (9).

In the eccentric phase, there were no significant differences between the 3 exercises, although the pectoralis major showed greater activation in the front pulldown (9).

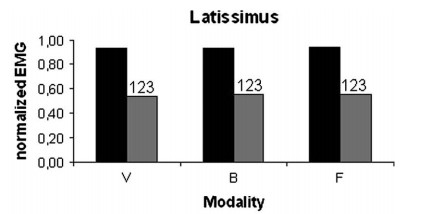

Muscle activation of the latissimus dorsi

Below we see the muscle activation of the latissimus dorsi in the concentric and eccentric phases of the behind-the-neck pulldown.

If we analyze the attached graph, we can observe that the activation of the latissimus dorsi, both in the concentric and eccentric phases of the 3 exercises, is practically the same (9).

Therefore, the latissimus dorsi has very similar activation in the front pulldown, the behind-the-neck pulldown, and the V-bar pulldown (in the concentric and eccentric phases) (9).

Michael (2003) observed that in the front pulldown, the upper fibers of the latissimus dorsi show a higher percentage of activation than in the behind-the-neck pulldown.

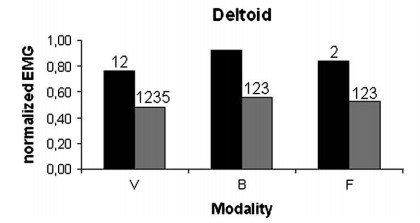

Muscle activation of the posterior deltoid

Below we see the muscle activation of the posterior deltoid in the concentric and eccentric phases of the behind-the-neck pulldown.

Regarding the muscle activation of the posterior deltoid, there were no significant differences in either the concentric or eccentric phase in any of the exercises (9).

However, we can observe that in the behind-the-neck pulldown, the posterior deltoid shows slightly higher activation than in the other exercises during the concentric phase (9).

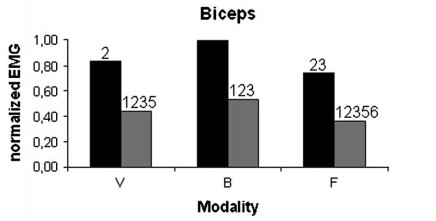

Muscle activation of the biceps brachii

Below we see the muscle activation of the biceps brachii in the concentric and eccentric phases of the behind-the-neck pulldown.

Sperandei et al. (2009) observed in their study that the biceps brachii showed a higher percentage of activation in the behind-the-neck pulldown during the concentric phase.

Even so, the differences compared to the front pulldown and the V-bar pulldown were not significant (9).

In the eccentric phase, there were no significant differences in the muscle activation of the biceps brachii between the 3 exercises (9).

Behind-the-neck pulldown and risk of injury

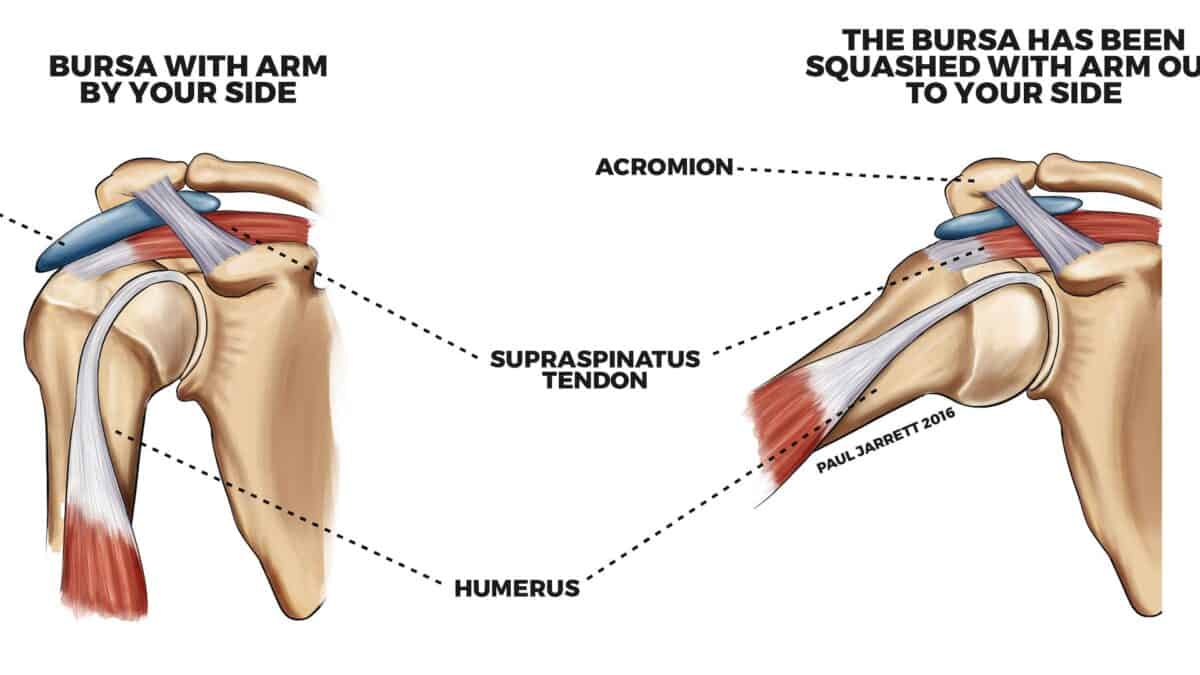

Recently, the behind-the-neck pulldown has been heavily criticized for the potential risk of injury it poses to the glenohumeral joint.

This is because the external shoulder rotation combined with abduction during the exercise execution puts the joint at risk by minimizing the stabilization capacity of the rotator cuff and leaving the glenohumeral joint under very high stress (5).

This situation is worsened by having to perform a horizontal shoulder abduction to prevent the bar from touching the performer’s head (5).

Additionally, some people lean forward while performing the exercise, causing greater external rotation and horizontal abduction, which can increase the chances of injury (5).

Michael (2003) states that this position of the glenohumeral joint could lead to anterior glenohumeral dislocation, anterior glenohumeral instability, and/or impingement.

If we compare the behind-the-neck pulldown with the front pulldown, in the latter, the exercise is performed in the scapular plane where there is greater contact between the joint surfaces, less stress on the glenohumeral ligaments, and better functionality in the rotator cuff (5).

This makes the front pulldown a safer, more functional exercise with a greater range of motion during its execution.

Why could we do without the behind-the-neck pulldown in our training?

If we observe the action of the muscles involved in the front pulldown and the behind-the-neck pulldown, we can conclude that it is practically the same (6, 7).

However, there are authors like Michael (2003) who inform us that in the front pulldown there is a greater activation of the latissimus dorsi due to greater internal shoulder rotation.

But, as we have seen earlier, in the behind-the-neck pulldown, the shoulder position causes greater stress on the capsule and the glenohumeral ligaments, which increases the chances of the performer getting injured (2, 4, 6).

Therefore, the fact that the muscle activation patterns are very similar in the front pulldown and the behind-the-neck pulldown and considering that the behind-the-neck pulldown is harmful, suggests that especially in health contexts, the front pulldown should replace the behind-the-neck pulldown in our training programs.

Normally, in a health training context, trained individuals will not have great shoulder mobility to withstand the stress that the behind-the-neck pulldown causes to the glenohumeral joint.

For this reason, we would prioritize the use of the front pulldown.

However, in a high-performance sports context such as weightlifting, the behind-the-neck pulldown could be used because the athletes’ shoulders will be more prepared to withstand stressful situations.

Even so, this exercise still carries a higher risk of injury than the front pulldown.

Conclusions

The front pulldown and the behind-the-neck pulldown have very similar muscle activation patterns.

The behind-the-neck pulldown increases the chances of injury to the glenohumeral joint due to the joint position during the exercise execution, where it endures great stress.

In a health context, the behind-the-neck pulldown should be discarded and replaced with the front pulldown.

However, in a sports performance context and depending on the sports discipline, this exercise could be performed as the athlete’s shoulder joint is likely more prepared for it.

Podcast “Behind-the-neck pulldown: A dispensable exercise”: Play in new window |

Subscribe to Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google Podcasts |

Bibliographic references

- Carpenter, CS, Novaes, J, and Batista, LA. Comparison between the behind-the-neck and front pulldown according to electromyographic activation. Rev Ed Fis 136: 20–27, 2007.

- Crate, T (1997). Analysis of the lat pulldown. Strength Cond 19: 26–29.

- Delavier, F. (2018). Guide to muscle movements (6th ed.). Paidotribo.

- Gross, ML, Brenner, SL, Esformes, I, and Sonzogni, JJ (1993). Anterior shoulder instability in weight lifters. Am J Sports Med 21: 599–603.

- Michael, G. (2003). A Biomechanical comparison of the front and rear lat pull-down exercise.

- Reeves, RK, Laskowski, ER, and Smith, J. Weight training injuries. Part I. Phys Sportsmed 26: 67–83, 1998.

- Reeves, RK, Laskowski, ER, and Smith, J. Weight training injuries. Part II. Phys Sportsmed 26: 54–63, 1998.

- Signorile JF, Zink AJ, Szwed SP. A comparative electromyographical investigation of muscle utilization patterns using various hand positions during the lat pull-down. J Strength Cond Res. 2002 Nov;16(4):539-46. PMID: 12423182.

- Sperandei S, Barros MA, Silveira-Júnior PC, Oliveira CG. Electromyographic analysis of three different types of lat pull-down. J Strength Cond Res. 2009 Oct;23(7):2033-8. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b8d30a. PMID: 19855327.