The phenomenon of the Sticking point in basic exercises has been investigated, it is a position in the lift where it cannot be completed, this article deals with the Sticking point in the three basics.

What is the Sticking point and how to improve it?

Since the Sticking point was first observed in lifting, this event has been the subject of multiple studies to observe the causes of why this phenomenon occurs, and from this point establish strategies in strength training with the aim of achieving continuous improvement.

That is why the Sticking point, known as the sticking point at a moment in the lift, or as Kompf, J., & Arandjelović, O. (2017) put it

The position in the range of motion of a lift where a disproportionately large increase in the difficulty associated with continuing the lift is experienced.

This article offers the possibility of knowing what the sticking points are in exercises such as squat, bench press, and deadlift, and establishing different strategies to offer continuous improvement in these exercises.

In other words, two important points are observed in the Sticking point; the first is muscular failure and the second is a biomechanical weakness of the technique due to lack of work at some point in the lift (1 and 2).

On the other hand, the possibility of an injury occurring due to overexertion at the Sticking point could be likely, so the goal of every trainer is to strengthen those weaknesses associated with the lift (1 and 2).

On the other hand, the Sticking point is multifactorial, which requires careful prescription of exercise selection for each case. Since the Sticking point occurs purely due to performance or the appearance of a weak link, which if not treated correctly as the form of the exercise deteriorates and the high demand could lead to an injury (2).

In the same line, the treatment based on the exercises is different from the conventional exercises that are known (2).

Physiological and biomechanical mechanisms that appear in the Sticking point

With the aim of developing a strategy that seeks to explain the phenomenon of the Sticking point, and improve the quality of lifts in this segment, we will address the main physiological and biomechanical mechanisms that occur in relation to the Sticking point.

Within muscle strength, action against a mobile or immobile resistance, the muscular, skeletal, and articular systems interact, with which at the muscular level the number of sarcomeres and the cross-sectional area play a very important role, as well as the angle of pennation and the work of the tendons (1).

Regarding the force-length relationship, this will depend on the shortening and stretching capacity of the involved musculature, after which the force that a lifter can apply against the bar varies throughout the lift in a way independent of leverage changes due to the biomechanics of the lift (1).

Therefore, the force-velocity relationship will depend on the rate of change of muscle length at the time of the lift, which the increase in speed requires high levels of force (1).

Another factor that appears in the Sticking point is fatigue, which will depend on the magnitude of the force and its duration, and the capacity of the central, peripheral nervous system, and the energy substrates required for the lift (1).

The force of muscle contraction as a capacity for fiber recruitment will depend on the frequency of stimuli from the motor nerves and the number of “activated” fibers (1).

In the muscle, the type I fibers which are the slowest and are stimulated first, and the type II fibers, the fastest, are recruited as the resistance is greater (1).

Another aspect to consider is the torsion or torque effort, with which in the Sticking point three fundamental points are affected, at the muscular level (I) the force produced by the muscle, (II) the angle of the direction of the force in relation to the distance of the resistance, and (III) the point where the force is applied.

That said, as seen in the image, when analyzing these points, in a squat the Sticking point occurs at 90º of knee flexion, in bench press at the bar’s exit from the chest, at 90º of elbows or at the end of elbow extension, while in the deadlift the bar is at thigh height, without the possibility of “closing the movement” (8).

In each lift, biomechanical disadvantages appear, such as the length of the limbs, the structural body mechanics of the lifters, isometric strength (currently debated), changes in bar load, number of contributing muscles, changes in external and internal levers (2 and 3).

Sticking point in the squat, why does it occur?

To mention some main characteristics of the squat, knowing that more muscle groups are involved, but the main ones involved are the lower body, such as the ankle, knee, and hip joints, which when performing this exercise with the bar on the back, what is expected is that in different variants the movement can be completed correctly.

In the squat, the most important points are the interaction of the squat adoption by the athlete, their biomechanics and execution technique, and the point of greatest Sticking point that the lifter presents, as this varies from one to another, and the level of muscle activity, but to affirm this last point more studies are needed (1).

Strategies to overcome the Sticking point in the squat

When the external load exceeds the possibility of force production, and this action leads to difficulty in completing the movement, some common errors appear that require exhaustive analysis.

After which, Costa, E. and Milo, J (2024), mention that due to the lack of strength in the quadriceps, complete knee extension is not achieved, and this makes it difficult to finish the movement, or another frequent error is the pronounced elevation of the glutes which leads to the bar moving forward and not upward.

That is why useful strategies must be aimed at each athlete, for example working on hip and ankle mobility and flexibility since the limitation of these two points would not allow achieving the desired depth (8).

Focus on the neutral gaze, with the torso and chest in a neutral position, this will prevent looking down and the back from losing tension. Work on strengthening all the involved musculature, especially glutes and quadriceps.

That said, aiming at variants that each individual requires will be one of the ways to overcome the Sticking point, such as the high bar squat (promoting a more upright torso), the low bar squat (where the participation of the posterior chain increases), the safety bar squat (promoting a more comfortable grip), belt squat (promoting hip strength and not back strength), and goblet squat (which can serve as a preparatory or warm-up exercise) (8).

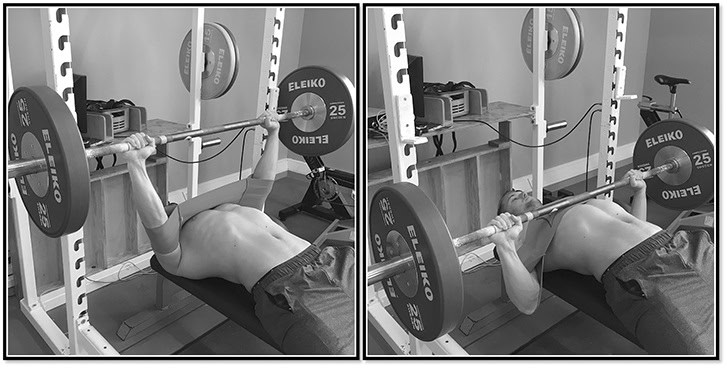

Sticking point in the bench press, why does it occur?

Another of the basic exercises is the bench press, commonly known for strengthening the pectoral, shoulder, and triceps muscles and to a lesser extent the brachial biceps, here it will depend on the scapular and arm work, as well as the grip width, the biomechanics of the lifter, and the execution style they prefer.

For this exercise, the Sticking point is the most studied of the three, as Wilson and Elliott and collaborators cited in Kompf, J., & Arandjelović, O. (2017), announce that the Sticking point occurs in the first phase of the lift at 30° of the bar’s exit from the chest with maximum loads.

On the other hand, it is observed that the grip width also influences the Sticking point, with which Król and collaborators cited in Kompf, J., & Arandjelović, O. (2017), mention that the Sticking point occurs in the ascending phase of the bar, which coincides with Dugdale, J. H and collaborators (2019), as the second phase of the lift.

Understanding the 3 phases of the Sticking point in the bench press

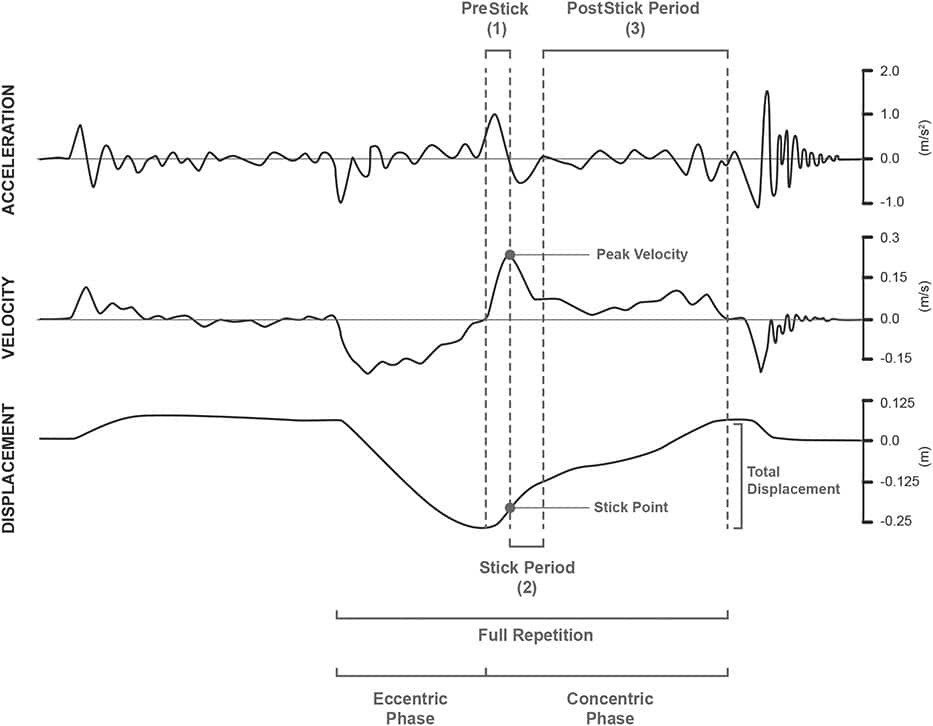

In the graph below, the phases in the bench press with the use of slingshot and the phases of the Sticking point are observed, as proposed by Dugdale, J. H and collaborators (2019), in the attempt of 1 maximum repetition (RM).

The first phase of the Sticking point is the eccentric action phase, where the execution speed is zero. For the phase 2, it is characterized by the fast action of the bar in the concentric action. And the end of phase 3, culminates at the end of the concentric action, that is, in the final extension of the triceps.

That said, the bench press presents certain phases of the Sticking point, especially the bar’s exit from the chest, the ascending path of the bar with the elbows at 90º, and the final concentric phase of the final elbow extension (8).

For this, the “Sticking point period” is defined by van den Tillaar, R., & Ettema, G. (2010), as the period of deceleration of the bar’s ascending movement, with the highest speed reaching a Sticking point where a loss of that speed is observed, known as lowest local speed.

So, what does this statement mean? It means that the bar stops at a point in the path and stays at that point without being able to complete the repetition.

The sticking in the bench occurs with 90% of the load, as it was evidenced that with lighter loads these Sticking point periods do not occur.

Tillaar, R., & Ettema, G. (2010)

Relationship of maximum repetition (RM) with body mass

Another interesting point is the body mass expressed in kilograms, which lifters with greater body weight after weeks of training would manage to lift greater weights, it will also depend on their body structure (3 and 4).

[article ids=”94953″] This statement coincides with what Dugdale, J. H and collaborators (2019) mention, in this study it was correlated that athletes who weighed more and had a body mass of more kilograms of body weight lifted even more weight in the bench press bar with slingshot (3).

In other words, the use of slingshot with loads between 85% and 120% of the conventional bench press RM, as a strategy for improvement and strengthens the dominant and non-dominant side of the upper body, which at the time of performing the push this concern of many trainers and athletes would be benefited (7).

Use of slingshot as a strategy to overcome the Sticking point

The slingshot is used to perform bench press, it makes a “unloading” effect on the triceps muscle, which allows implementing or maintaining the execution speed against submaximal, maximal, or fatigued loads, it is used in powerlifting, to get out of the Sticking point zone or with the aim of strength gains (3, 4, and 5).

It is used for strength and hypertrophy gains of the upper body, in addition to being used for sports purposes to improve swimming, throwing, or rowing in a kayak (3).

But following the line of using the slingshot, it is used by weightlifters to get out of a plateau, to improve bench press loads, or to improve execution speed in the 1RM under submaximal or maximal strength conditions (3).

Main characteristics of the slingshot

The execution of the bench press consists of phases, in which there is a Sticking point, represented by eccentric and concentric actions and by the main characteristics of the movement execution.

It is here where Dugdale, J. H and collaborators (2019), mention the main characteristics that occur at the level of mechanical action and muscle work of the involved musculature (especially the brachial triceps), the relationship of the lifted kilos with body mass, and the peak effort.

One way to use training programming with the aim of improving the bench press is to work with the assistance band combined with a common bench press with the aim of strength gains.

Within the sports field, the slingshot is used to lift greater weights compared to not using it, or to increase execution speed with the same weight used in the “Raw” modality in weightlifting.

In addition, it was documented that this type of equipment in weightlifters increased the bench press load by 16 to 20 kilos more than their RM, which could bring about the sensation of using heavier loads supported in the hands (3 and 5).

The 1RM “Raw” closely corresponded to 3 repetitions with calculated Slingshot.

Dugdale, J. H and collaborators (2019)

For this, it is essential that the slingshot is placed correctly, that is, the band covers both elbows and passes at chest height, respecting the body proportions of the subjects using it (5 and 6).

On the other hand, the slingshot manufacturers mention that it is a band with an elastic function that is placed on the elbows, printing elastic force and pressure on the involved musculature, which allows reducing tension on the elbows and shoulders (4).

On the other hand, the slingshot would allow using supra-maximal loads, that is, more than 100% of the conventional or competition bench press load (6).

Execution speed and effort capacity

One of the most important points is that the athlete exerts the greatest possible effort, as the use of this equipment will allow adding greater execution speed compared to a raw bench press (4).

In addition, in this study by Wojdala, G. and collaborators (2020), it was observed that the use of this equipment allows lifting 3 times more the weight of 1RM Raw and with greater speed.

On the other hand, in relation to execution speed and movement mechanics, the use of slingshot seems to offer a good arm (triceps) position to achieve completing the concentric action.

Benefits of using the slingshot

Many of the benefits provided by this band focus on executing the movement with good technique and confidence, here Wojdala, G., and collaborators (2020) and later the same author in (2022), agree on these benefits provided by the use of slingshot.

It provides greater stability: as the band exerts tension and pressure on the involved muscles, and this allows the movement to be more stable.

It acts in printing less pressure on the shoulders and elbows, as by providing stability, it offers security for these joints.

It allows working throughout the ROM in case of injury, as if it is a minor injury, training can continue with the necessary care.

It helps in the rehabilitation process in minor injuries, as it offers less tension at the muscular level, and allows providing greater confidence to the user.

Familiarize with supra-maximal loads, as this material offers the opportunity to train with loads higher than 100% of the conventional or Raw bench press.

Give confidence to oneself, as it offers the possibility of having the sensation of greater control of the used load, technique, and weight in the hands.

It focuses on the development of strength and power, as this band offers to use loads above 90%, allowing maintaining or increasing execution speed.

It helps to maintain or improve execution speed, as it is a determining and important aspect in the bench press.

Improves the dominant and non-dominant side, one of the major concerns of trainers and athletes, to prevent the bar from having a path with little alignment.

For these benefits to occur, the authors mention that it is important to first know the element, be adapted to the exercise, have experience in it, or at least have practiced it already with a year of uninterrupted training.

Precautions in the use of the slingshot

It is known that the slingshot has multiple benefits, but for these to occur, precautions are essential, like everything in the gym, for this reason, Wojdala, G., and collaborators (2020) and later the same author in (2022).

Start with a familiarization process, as the first days of use may become uncomfortable or difficult to settle on the bench and take the bar.

At a minimum, the authors mention that the trained person should have a year of uninterrupted experience in strength training, as they will manage to familiarize themselves even better with the element.

The anthropometric characteristics vary from person to person, so the size of the element must be adapted to the body proportions of the lifters.

The use of the assistance band, in experienced and competitive level athletes, will offer the possibility of training with supra-maximal loads, that is, exceeding 100% of the conventional bench press, for this reason, greater work of stability of all the musculature, strength, and hypertrophy will be required.

Finally, it is not a precaution but a way to execute it, as long as the bar does not bounce on the chest, the bench press movement can be used by pausing or not the bar on the chest.

Muscle activity with the use of slingshot

The assistance band in the bench press would allow printing less effort from the bar’s exit from the chest and from the last part of the concentric action the effort will be even greater (3).

In addition, it was discovered that the activity of the pectoral and anterior deltoid was the same as with the assistance band, but compared to the raw modality, the triceps will have greater participation than with the use of the assistance band (3).

That said, with loads exceeding 90%, it is apparent and evident to the eye that “mechanical disadvantages” begin to appear, observing that the bar loses the form of displacement, loses technical form, or that the arms and shoulders lose position (4).

For this point, and many more, the slingshot would seem to have a wide advantage to correct those technical deficiencies (5).

In the same line, the research by Wojdala, G. and collaborators (2020), detected that the main muscle groups had little activity but with loads near 100% the muscle activity was greater.

That said, when training with loads above 100% of the conventional bench press, it is worth highlighting the work of strength, stability, and hypertrophy of all the involved musculature in the bench press to perform it stably, strongly, without imbalances, and with a lot of stability (6).

Programming the bench press with Slingshot to overcome the Sticking point

In the first measure, adjust the height of the flat bench to the desired height of the lifter, adjust the grip width depending on comfort, preferences, or anthropometric proportions.

Once the previous step is done, work on familiarizing with the element, that is, perform series and repetitions with 70% of the raw bench press (without slingshot).

That said, Dugdale, J. H and collaborators (2019), mention that to select the slingshot load it is necessary to have the 1RM load, of bench press and based on those kilos start programming (always considering that this element can provide 16 kilos more).

- Familiarize with the use of the element, adjusting the height of the bench and the grip width.

- Perform the warm-up, without reaching fatigue with 2-minute rests, seeking series of 5 to 8 repetitions at 70%.

- Perform the programmed series, with a maximum of 3 repetitions at 87.5% maximum.

Two aspects that the authors mention for this type of work is to use the regulatory standards of powerlifting and perform each repetition with the maximum possible capacity.

In another context, in the bench press, the Sticking point can occur at the end of the concentric phase, which following the line of Dugdale, J. H and collaborators (2019), could be taken as a strategy to use the programming form that these authors propose.

- For example, use a frequency of twice a week, with which to try on day one to perform regulatory raw bench press and a second day with the assistance band.

Perform an upper body warm-up, as a general warm-up, then plan series with 3 to 5 minutes of rest, and in the case of seeking 1RM increase each successful series by 2.5 kilos or lower the same weight if the series is not successful (4).

- 2 series of 6 repetitions at 40%.

- 1 series of 3 repetitions at 60%.

- 1 series of 2 repetitions at 75%.

- 1 series of 2 repetitions at 85%.

In this way of planning, ensure that the trained individuals have more than a year of experience with the exercise.

On the other hand, with the aim of muscle mass and strength gains, Bellar, D. M. and collaborators (2011), propose training the bench press 2 times a week for 13 weeks, one raw variant and another variant with slingshot, where this with a progression from week to week until achieving 5 series of 5 repetitions at 85% with more than 90 minutes of rest.

Another way of programming with the use of Slingshot is the use of approach loads for the 1RM test, which is proposed by Wojdala, G. and collaborators (2020), where they suggest the following points:

- General warm-up of 5 minutes with an ergometer, and at this point, upper body mobility work could be added.

- For the specific warm-up, various work percentages are used

- 1 series of 15 repetitions at 20%, 1 series of 10 repetitions at 40%, and 1 series of 5 repetitions at 60%.

- Subsequently, the 1RM test begins starting with a load at 70%, 85%, and 100%, and at this point, the authors mention that for each series the kilos on the bar increase from 2.5 to 10 kilos depending on the execution and speed of the bar movement.

It is worth noting that this type of programming is with trained individuals who have more than three years of experience, not only in weightlifting but also in competitions.

Strategies to achieve an effective bench press and overcome the Sticking point

As analyzed, the three most common phases of the Sticking point in the bench press are near the chest, halfway where the elbows are at 90°, and during the last part of the path, that is why observation is essential to improve the three basics, and even more so the bench press as a large part of the population has difficulties progressing in kilos in this exercise.

Therefore, the strategies to improve the bench press are to push the floor well with both feet supported, specifically strengthen pectorals, triceps, and stabilizing musculature, use analytical work with bands, permanently correct the technique, and of course develop specific strength in the three phases or where the athlete presents the Sticking point (8).

Within the variants that can be used is the competition bench press (improving the specific technique applied to the federation’s regulation that is represented), bench press with elevated legs (avoiding arching with a more concrete focus on the chest), floor press (focusing the work on the triceps), flat bench with close grip (putting more emphasis on the triceps), flat bench with wide grip (increasing work on the extensor part of the pectoral) and flat bench with reverse grip (interesting to vary the routine) (8).

Sticking point in the deadlift, why does it occur?

[article ids=”95490″] The deadlift, unlike the squat and bench press, the movement begins with the bar on the ground, with which regardless of the type of variant chosen, the hip joint is the one that acts the most in this movement, and the main characteristic is lifting the bar from the ground to the line of the thighs with the back fully upright and looking forward.

Regarding the Sticking point, the deadlift has received less attention compared to the other two, but the most notable Sticking point is when the bar is at thigh height and the movement cannot be completed (1).

That said, 3 phases are observed in the deadlift:

- In phase 1 the knee extension.

- In phase 2 the hip extension.

- In phase 3 the hip and knee extension at the same time.

With which in the deadlift the Sticking point is due to one of the difficulties in the “bar block”, isometric muscle actions, at the biomechanical and physiological level of the lifter (1).

Strategies to overcome the Sticking point in the deadlift

Here you must work and build a strong and solid core, incorporate exercises to improve back strength, use deficits, bands, chains, rack pulls, or good mornings, with the aim of strengthening the posterior chain.

Another interesting point is to strengthen the type of grip chosen by the lifter, identify if they are a puller or pusher, and strengthen all possible variants.

With this, we can strengthen the Sticking point of the deadlift, whether in the first part of the lift (where the bar does not rise beyond knee height), the second part of the lift (around knee height), from the middle of the thigh or lack of grip strengthening (8).

Strategies to overcome the Sticking point

As mentioned, the Sticking point is multifactorial, and it will depend on several factors that are specific to the athlete and the exercise, which this point will allow addressing different strategies to best address the Sticking point, and that strategy is the best for each case and for each athlete.

For this, Kompf, J., & Arandjelović, O. (2016), propose 5 strategies to overcome the Sticking point.

Aim at isolation work with the aim of strengthening the musculature and train the muscle or muscle group in isolation, considering that in the Sticking point it can be seen as the weakest link, for example in the bench press a specific work of elbow extensor, or to improve the bench press exit, work with pauses of the bar resting on the chest.

Training aiming at the specific ROM with partial repetitions, where it can improve the lift by 10 to 20°, in addition to including isometric training (for example pushing a bar against an immobile resistance like a rack).

Develop the pre-Sticking point momentum, improving the athletes’ force rate with speed work with loads of 50 to 60% of the 1RM, with rests between 45 seconds to a minute.

Modify the exercise technique, seeking to change the context of the biomechanics of it, for example, changes in grip width, in the way of positioning in the bench press, varying the bar position in the squat, or using pauses or blocks in the deadlift.

Use accommodated resistances or other variables, as the use of bands would allow the learner different sensations such as ease or difficulty in the exercise, use of chains on the bar, or adjust the load in the final part of the movement, that is, increase the weight even more, for example in a squat with a high box, in a bench press with a block, or in a deadlift with a block, as these strategies would allow blocking or closing the movement, and overcoming the Sticking point.

Final conclusions on Sticking point

Considering the results of the mentioned investigations, it can be concluded in this article where the Sticking point of the three basics of strength training was presented, based on the literature and presenting a strategy in training programming to overcome the Sticking point and strengthen weaker aspects to achieve “closing” the movement.

Therefore, the complete understanding of the Sticking point of each movement will require consideration of all these factors and an explanation of a particular Sticking point, which requires an exhaustive analysis of the particular lifter in the context in which the Sticking point of each movement is observed (2).

Bibliographic references

- Kompf, J., Arandjelović, O. (2017). The sticking point in the bench press, squat, and deadlift: similarities and differences, and their importance for research and practice. Sports Med 47, 631–640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0615-9.

- Kompf, J., & Arandjelović, O. (2016). Understanding and Overcoming the Sticking Point in Resistance Exercise. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 46(6), 751–762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0460-2.

- Dugdale, J. H., Hunter, A. M., Di Virgilio, T. G., Macgregor, L. J., & Hamilton, D. L. (2019). Influence of the “Slingshot” Bench Press Training Aid on Bench Press Kinematics and Neuromuscular Activity in Competitive Powerlifters. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 33(2), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001853.

-

van den Tillaar, R., & Ettema, G. (2010). The “sticking period” in a maximum bench press. Journal of sports sciences, 28(5), 529–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640411003628022.

-

Bellar, D. M., Muller, M. D., Barkley, J. E., Kim, C. H., Ida, K., Ryan, E. J., Bliss, M. V., & Glickman, E. L. (2011). The effects of combined elastic- and free-weight tension vs. free-weight tension on one-repetition maximum strength in the bench press. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 25(2), 459–463. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c1f8b6.

-

Wojdala, G., Golas, A., Krzysztofik, M., Lockie, R. G., Roczniok, R., Zajac, A., & Wilk, M. (2020). Impact of the “Sling Shot” Supportive Device on Upper-Body Neuromuscular Activity during the Bench Press Exercise. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(20), 7695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207695.

-

Wojdala, G., Trybulski, R., Bichowska, M., & Krzysztofik, M. (2022). A Comparison of Electromyographic Inter-Limb Asymmetry During a Standard Versus a Sling Shot Assisted Bench Press Exercise. Journal of human kinetics, 83, 223–234. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2022-0084.

- Costa, E. and Milo, J (2024). The power of strength. Health, fitness, sport, and high performance. 1st ed – Autonomous City of Buenos Aires: JMILO Ediciones, 2024. Digital book, PDF.