In the following article we will talk in detail about the FMS Functional Movement Assessment test, or by its initials in English Functional Movement Screen. A brief explanation will be given about its importance in assessing movement quality (which we already addressed in a first installment), application methods, and practical examples will be outlined to ensure it is understood as best as possible.

On the other hand, the points to analyze in this test will be explained in detail, which, based on quantifiable variables, will allow us to detect possible muscle imbalances, misalignments, and mechanical imbalances in the subjects.

Beginnings in the application of the FMS Functional Movement Assessment test

The FMS test was created in 2006 by the authors Gray Cook, Lee Burton, and Barbara Hoogenboom, who published the first original articles on the use of Fundamental Movements pre-exercise as an assessment of movement functionality. From these publications, the authors (1, 2) extended their proposal as an efficient way to conduct a proper evaluation in the field of exercise science and health. It has been subjected to numerous modifications, criticisms, and/or praises from different contexts and professionals (3).

From here, these evaluations are used in multiple sports as an efficient way to assess movement quality (4). Being essential in the processes to improve the biomechanical technique of a sport, core stabilization, movement economy, motor control, and above all, the effectiveness and prevention of injuries. This does not mean that its use in gyms and recreational centers is not of utmost importance, even though observational skills play a vital role in a trained professional. Functional movement assessment is extremely necessary to specifically detect muscle shortening, asymmetries, and movement imbalances, to efficiently address the problem through appropriate exercises.

Relevant aspects of the FMS Functional Movement Assessment test

The main intention of this test is to identify pathologies/dysfunctions early within a specific group or subject. Therefore, we can affirm that it is a test used to detect certain dysfunctions of the movement system. On the other hand, it is worth clarifying that its authors propose it purely as an “assessment or evaluation” of the subject’s functional state, rather than as an examination of functional movement exploration (5). The FMS is a practical system or tool that allows the professional to evaluate the basic fundamental movement patterns of a given individual. Almost or equally important as evaluating body composition.

This functional movement assessment battery can be a very effective method to identify the markers that describe a “basic functional body.” Likewise, this system can also be used in multiple fields, such as in rehabilitation, to determine if an athlete is ready to return to training or ultimately to evaluate the functional capacity of a conventional subject (6).

Objective of the tests that make up the FMS Functional Movement Assessment test

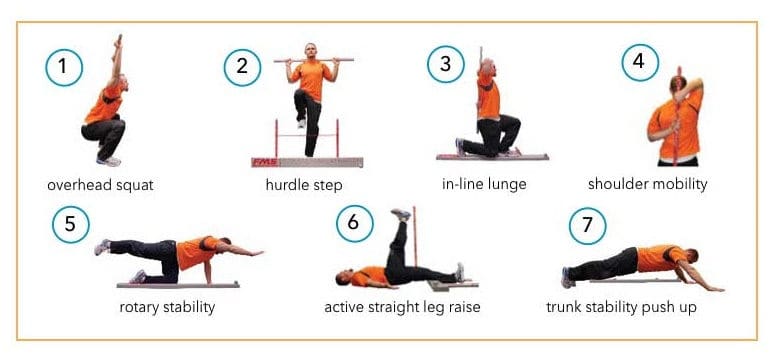

The functional movement assessment test or FMS is composed of seven fundamental/basic movement patterns or tests. As Craig Lieberson states, each movement-exercise is a test (7). Within these tests, the evaluation of mobility, stability, and motor control is highlighted.

According to its authors Gray Cook, Lee Burton, and Barbara Hoogenboom, these fundamental movement patterns are designed to provide a quantifiable and observable performance of certain basic movements. The tests expose the subject to positions where weaknesses, imbalances, and muscle overcompensations are exposed, where consequently the lack of appropriate stability and mobility becomes evident. Thus, through these tests, it is intended to analyze bilateral imbalances as well as the mobility-stability of the subject. In such a way as to be able to address a training plan more efficiently, for example oriented towards strength and work on muscle deficits and imbalances.

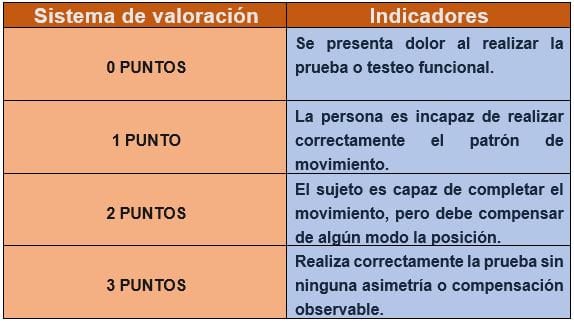

Scoring method of the FMS Functional Movement Assessment to measure the evaluation

The basic scoring method is based on observational aspects, where each of the seven tests or assessments performed is rated from zero to three points. Ultimately determining by summation the results of the movement quality of the evaluated subject. Three points determine the best possible score, while zero points the worst when pain is manifested in any of the tests during its execution.

The seven tests allow for execution, and therefore a determined score. This must be performed bilaterally to detect any possible asymmetry. The lowest value of both sides is always considered valid for the total sum of 21 points. It is worth clarifying that a higher score is not necessarily better.

Description and analysis of the movements/exercises that make up the FMS Functional Movement Assessment

Next, we will analyze each exercise or test, explaining in detail each test that makes up the FMS test. In this way, we will try to globally address the most effective way to use this functional movement assessment tool. It is worth noting that, once each test is performed, opting for the use of goniometers, editing software, and postural assessment tools will give our work a richer content analysis. Ultimately, not only relying on the FMS score but trying to find more specific solutions through a correct and specific data analysis. In a third installment, we will test this battery of tests on several subjects, in order to provide more practical results.

Deep Squat or overhead squat (first movement pattern)

The deep squat Overhead squat is a test that involves the mechanics of the whole body and a great general neuromuscular control. Good coordination of the limbs, core stability with the hips and shoulders in symmetrical positions must be present. The deep squat seeks to evaluate the mobility of the hips, knees, and ankles bilaterally, symmetrically, and functionally. The stick used above the head evaluates the stability, bilaterality, or symmetry of the shoulders, scapular region, and thoracic spine.

To perform this exercise, the feet should be in the sagittal plane pointing forward. Then the athlete takes the stick above their head, adjusting the arm separation position to form a 90° angle. Then, the stick is pressed over the head with the shoulders flexed and abducted, with the elbows fully extended. Subsequently, the athlete begins to slowly descend into a squat position as deep as possible, with the heels on the ground, head, and chest forward.

In this test, up to three repetitions can be performed, but if the first does not achieve a score of three points, it is not necessary to perform the other repetitions. If the criteria for a score of three points are not met, the athlete is asked to perform the test on a 2×6 board under their heels. If after the modification, the subject still does not perform the gesture correctly, they receive a score of one point if no pain is present.

Hurdle Step or hurdle passage (second movement pattern)

It is a movement that requires great motor control. Coordination and stability between hips and trunk during the movement are required, as well as balance and stability on the support leg. The hurdle step evaluates bilateral functional mobility and the stability of the lower kinematic links.

The exercise should start with the feet together, aligned touching the base of the hurdle. The hurdle is adjusted to the height of the anterior tibial tuberosity. A stick should be held behind the neck, and the athlete is asked to pass one leg over the hurdle and touch the ground with their heel while keeping the support leg extended. From there, the leg is moved to the starting position. Like the previous test, it should be performed three times and can be repeated on both sides.

It should be scored with three points if the hips, knees, and ankles remain aligned in the sagittal plane. No movements (or at least minimal) are noted in the lumbar spine. The stick and hurdle remain parallel. It will be scored with two points if alignment between the hips, knees, and ankles is lost. Movements are noted in the lumbar spine. The stick and hurdle do not remain parallel. Finally, it will be scored with one point if there is contact between the foot and the hurdle. A loss of balance is noted. And zero points if pain appears in the asymmetry of this movement.

Inline Lunge or inline lunge (third movement pattern)

The Inline Lunge is a movement pattern present in many sports actions. This movement pattern allows analyzing motor control, mobility, and core activity of the muscles involved in anti-rotation, lateral displacements, and changes of direction. Having a narrow base of support during its execution requires dynamic control of the pelvis and core.

To perform this exercise, the length of the anterior tibial tuberosity from the ground should be measured. Then the subject is asked to place their back foot at the end of the line and the heel of the opposite foot at the mark obtained from the tibial length. Then a stick is placed behind the neck, touching the head, dorsal spine, and sacrum. The stick is held at the cervical spine level with the hand opposite the foot that goes forward, while the other hand holds the stick at the lumbar spine level. The stick should remain vertical throughout the movement.

The movement starts with the flexion of the knees and hips. The rear knee should flex until it touches the line on the ground just behind the front foot’s heel and then ascend to reach the starting position. The test should be performed bilaterally and three repetitions should be executed on each side. Three points are obtained if the movement is not compensated and stability is maintained, two points for imbalances, and one point if the pattern is not correctly followed.

Shoulder mobility or bilateral shoulder mobility (fourth movement pattern)

This test is fundamental to assess bilateral shoulder mobility, detect weaknesses, muscle shortening, compensations, and instability of the glenohumeral joint structures.

To perform the test, the length of the hand should first be determined by measuring the distance from the wrist crease to the tip of the middle finger. Subsequently, each hand should be closed into a fist, placing the thumb inside the fist. During the test, the hands should remain in a fist and be placed on the back with a smooth movement. The evaluator should measure the distance between the fists. The shoulder mobility test should be performed three times bilaterally.

Poor performance during this test can result from several causes, the main one being a lack of external rotation, which is obtained from an increase at the expense of internal rotation favored by shoulders in antepulsion. Additionally, shortening of the pectoralis minor and latissimus dorsi can cause postural alterations. Finally, a scapulothoracic dysfunction may be present, resulting from decreased glenohumeral mobility followed by poor scapulothoracic mobility or stability.

Three points are given to the test if the distance between the fists is less than the distance marked from the wrist crease to the fingertip. If this distance becomes greater, this score decreases, finally if this distance is greater than one and a half of the first value obtained, a score of one point or less is given if there is pain.

Active straight leg raise or active straight leg raise (fifth movement pattern)

This test seeks to evaluate the dynamic mobility of the hip while simultaneously observing core stability and motor control of the trunk and pelvis, acting on a hip hinge with the leg.

In this exercise, it is observed how high a leg can be lifted while keeping it straight in a neutral position. On the other hand, the other leg must remain straight on the floor with the hip and foot in a neutral position. The movement stops and is marked at the point where either leg deviates from the setup position.

If the elevated leg surpasses the vertical line of the knee, three points are awarded, whereas if these change their initial position, this score decreases according to the limitation of movement and hip stability. This test should be performed a minimum of three times.

Trunk stability push up or trunk stability push up (sixth movement pattern)

The trunk stability push up is a very important test to recognize the level of stability possessed in the trunk’s kinematic chain. This requires a reflexive stabilization of the trunk as the arms apply the pushing force. It is important to clarify that if this test is not passed with a score of three points, it is very difficult to work with push ups or exercises with horizontal push movement patterns where body weight is manipulated.

In this test, a score of three points is obtained if the trunk stability is valid and presents good control. In case of extending the hip, arching the spine, and others, points will be deducted. This test should be performed at least three times for safety, in order to pay close attention to the stability of the spine in the movement and motor control.

Rotary stability or rotary stability (seventh movement pattern)

Rotary stability is the ability to control rotational forces, this through muscle mechanisms that work on an anti-rotation pattern. Rotary stability is necessary to resist rotation through the torso during arm and leg movements. The Bird-Dog exercise, for example, requires stability through the pelvis, core, and shoulder girdle during hip extension and shoulder flexion.

Rotary stability is what allows adequate motor control during complex movement patterns. To perform this pattern or exercise, it is important to start from a Bird-Dog position, or supporting knees with the femur at 90° in relation to the tibia, foot, and ground. The arms will also be at 90° in relation to the ground and trunk.

To obtain three points, hip extension and shoulder flexion must be performed with the members belonging to the same hemisphere, without presenting compensatory movements and instability. Two points and one can be obtained by performing the exercise but asymmetrically, that is, with crossed or opposite segments, where greater instability or possible pain can result in one point or zero.

Kinematic action and regional interdependence of movement

Each of the exercises represents a specific movement. A movement that requires appropriate kinematic action. The model that the authors use of the kinetic chain is used to analyze movement in general, representing the body as a linked system of interdependent segments.

The term “regional interdependence” is used to describe the relationship between specific regions of the body and how dysfunction in one region can affect a different region. In simple words, it determines that a poor movement pattern can lead to an injury or muscle imbalance.

The FMS test can be a good alternative to detect a decrease in proprioceptive information, which translates into deficits in movement quality. The result will be altered mobility and stability under the influence of asymmetries, shortening, and eventually leading to compensatory movement patterns.

Therefore, the FMS test would be an important tool in injury prevention and improving movement quality.

Research regarding the FMS functional movement assessment test

Since the first publications of the FMS battery, various investigations have emerged that have tried to study the inter and intra-evaluator reliability and validity of the FMS test scores. Gribble and collaborators (8) suggest that more familiar evaluators had greater intra-evaluator reliability (ICC = 0.95) compared to those with less experience (ICC= 0.37). Therefore, it is thought that the evaluator/administrator must be well trained with the tool.

Other studies, such as that of Kraus and collaborators (9), conclude that it should not be conceived as a unitary construct regarding the total sum of scores obtained to predict something as complex and multifactorial as injury risk. Since the individual components of the battery do not correlate with each other and therefore do not measure the same variable.

This makes it consider that it might be better to use and draw individual conclusions from each test or exercise separately. Despite this, the FMS can be a useful initial exploration tool for the locomotor system and analysis of basic movement patterns in subjects with low or moderate motor quality. In order to improve their movement quality and determine asymmetries, misalignments, and muscle shortening.

Another author investigated the central stabilization movement pattern. Okada and collaborators (10) found no significant correlation between the FMS test assessment and CORE stability, therefore, the tests used to measure “core stability” are not valid and direct measures of trunk kinematic chain stability. Finally, the correlations established for CORE stability, proposed for example by Stuart McGill (11), would have a greater relationship with the endurance component of the musculature and spinal stability.

Conclusions on the use of the FMS

The FMS test battery can be a more than useful tool to explore the functional asymmetries of the locomotor system and postural stability deficits. But like any tool, it requires familiarization, experience, and prior knowledge of it, in order to obtain greater validity in the results.

Despite this, the authors affirm that other types of tests and deeper and more specific evaluations are required in case of very low scores. This in order to find effective solutions to movement limitations and injury prevention.

On the other hand, it is clear that the functional asymmetries and postural or motor control deficits identified by the FMS will not always be contributing factors to injury, as other factors such as fatigue, competitive level, sports modality, and injury history are not taken into account, making this a multifactorial problem. Ultimately, even if a high overall FMS score is obtained, it does not mean that one is exempt from injury risk.

To conclude, in the words of Craig Liebenson, we can say that the FMS test battery is an excellent movement scenario that reveals certain key dysfunctions in movement”.

Here the importance lies in the professional analyzing the tool, practicing, gaining experience with the assessment and scoring system, and ultimately making the most of it to detect asymmetries, dysfunctions. Seeking to improve the movement quality of the subject in question and prevent future injuries.

Bibliographic References.

- Cook E. G. (2004). Athletic body in Balance: Optimal movement skills and conditioning for performance. Champaign,IL: Human Kinetics.

- Cook, Gray (2011). Movement: Functional Movement Systems. Screening—Assessment—Corrective Strategies. (link)

- Cook G, Burton L, Hoogenboom B. (2006). Pre-participation screening: The use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function.

- Ortiz, Jonathan (2018). Movement Quality and its evaluation. Digital magazine Mundo Entrenamiento. (link)

- Peña Guillermo, Heredia Juan Ramón, Segarra Víctor (2006). Functional Movement Screen (FMS) in the spotlight: What does science tell us?. IICEFS (link)

- Añon, Pablo (2013). The use of FMS (Functional Movement Screen) along with postural assessment, as a simple tool to detect injury risk and muscle imbalances in volleyball (4 parts). Digital magazine G-SE Entrenamiento. (link)

- Heredia Elvar J.R. (2013). Science and Practice Interview: its protagonists. Dr. Craig Liebenson “The importance of movement quality. Each movement-exercise is a test”. Digital magazine G-SE Entrenamiento.(link)

- Gribble P. A, Brigle J, Pietrosimone B. G. (2012). Intrarater reliability of the Functional Movement Screen. J Strength Condit.

- Kraus K, Schutz E, Taylor WR, Doyscher R. (2014) Efficacy of the functional movement screen: A review. J Strength Condit Res.

- Okada, T, Huxel, K. C, and Nesser, T. W. (2011). Relationship between core stability, functional movement, and performance. J Strength.

- McGill, S.M, Grenier, S, Kavcic, N, Cholewicki, J. (2003). Coordination of muscle activity to assure stability of the lumbar spine. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology.