Knowledge of the planes and axes of motion will allow us to analyze human movement, in this article we will discuss each one of them

To be able to analyze in a basic way the human movement, the knowledge of the planes and axes of motion is a great option in order to have a more accurate analysis of each movement or sporting gesture, so in this article we will explain the planes and axes of movement.

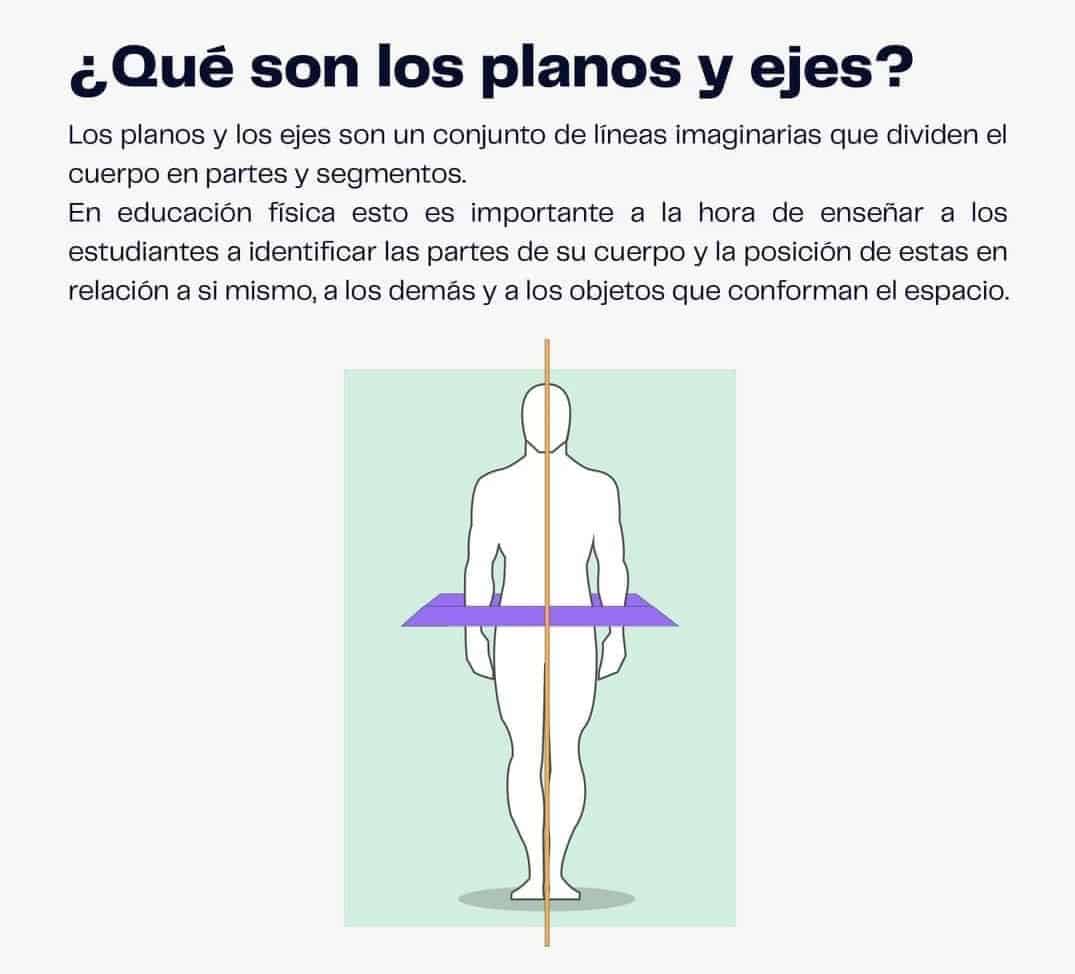

What are the planes and axes of motion?

The movement and its mastery, can be applied in the planes and axes of movement and from different areas, such as training and improvement of physical abilities such as strength, endurance and flexibility, or injury prevention or recovery and re-education of movement patterns of certain sporting gestures (6).

Therefore, to perform a certain movement analysis, Estrada Bonilla, Y. (2018), propose to follow some basic steps, in principle: locate and identify the joints or the joint to be analyzed.

Based on the planes and axes of motion, then identify a frame of reference, in which the movement is going to occur, in order to measure or observe it, then describe the change of position of the body segments, and finally describe and analyze whether the figure to be analyzed is in a state of dynamic or static equilibrium.

For this, Zarate Rodriguez, M and collaborators (2018), mention that the frame or reference system, is used to describe the movements of the body joints, using a three-dimensional reference such as the planes and axes of movement, starting from the anatomical position.

In addition, it is known that the individual is able to adopt different positions with his body in space, for this the standard anatomical position helps in its description. Once this position is defined, it is possible to locate and locate each part of the body, its organs and cavities, thanks to the planes and axes of movement (6).

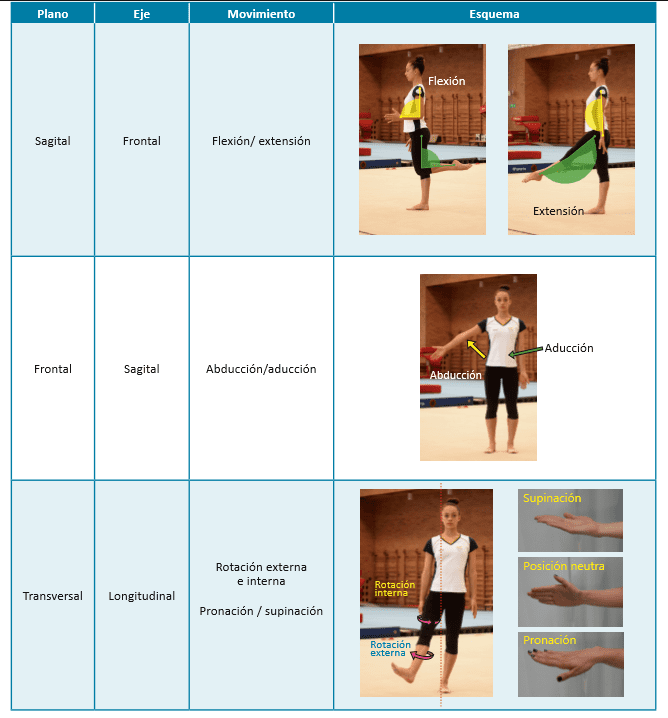

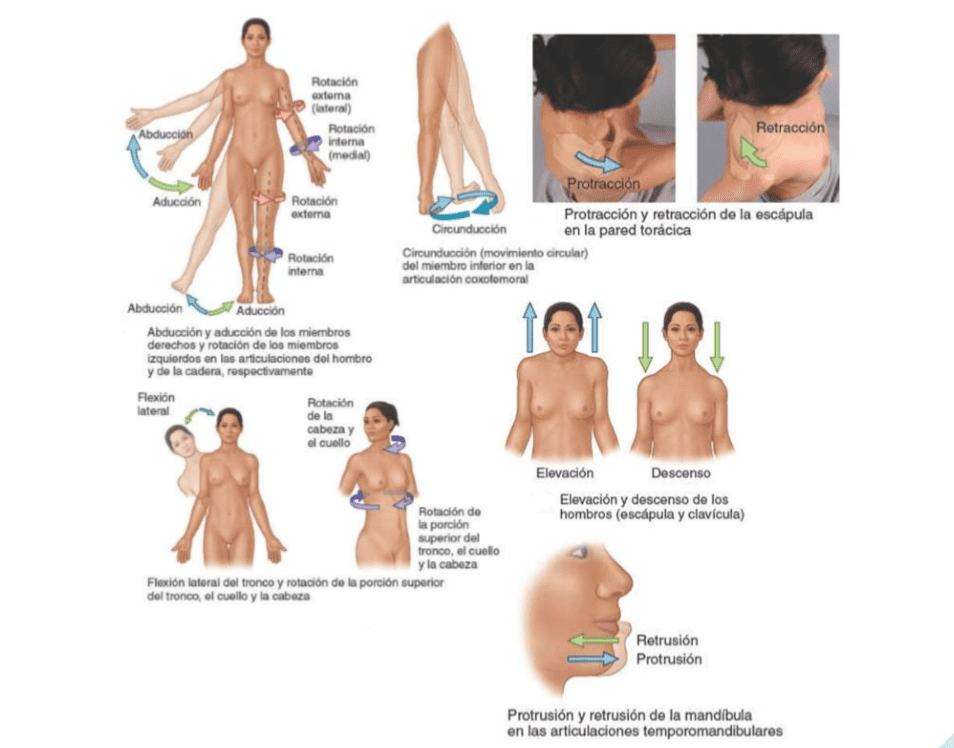

For this purpose, some of the movements that we can find in relation to the planes and axes of movement are flexion, extension, adduction, abduction and rotations.

.

What is anatomical position?

Before we get into the planes and axes of movement, let’s analyze the anatomical position.

This position is not usual, but it serves as a reference to take the movements as a starting point, and it is also taken into account that any position different from the anatomical position is considered a movement (1).

It also serves to trace the planes and axes of movement, and thus study and observe how the human body moves.

- For this purpose, the description of this position is based on the body structures. The body straight, with the feet together and parallel, the upper limbs placed laterally to the trunk or along the body, the forearms placed in supination, the coxofemoral in the position observed, the knees in extension, and the ankle at 90º (6, 7).

- In addition, it is the reference position to define and describe the planes and axes of movement of the human body (6, 7).

- Drake, R. L., et al. (2005), add that the facial expression should be neutral with the mouth closed and the eyes open, and with the gaze at a distant point.

Other postures to take into account are the decubitus positions , with the position lying face up or supine, or the position lying face down or prone (5).

.

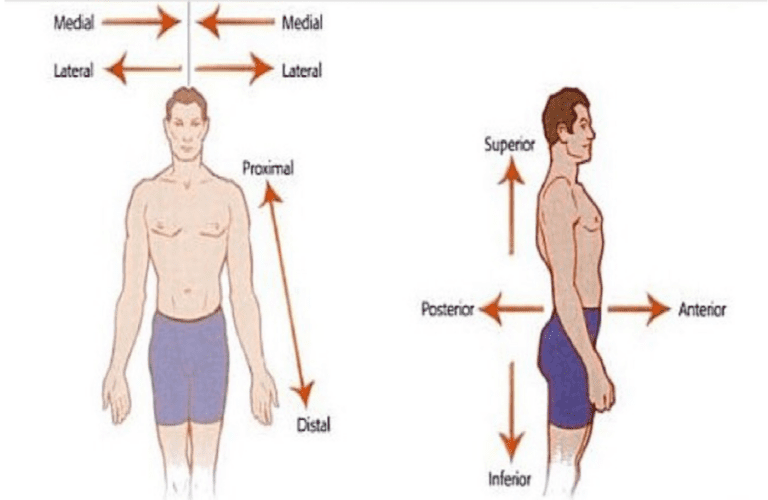

Guiding terms in relation to the planes and axes of motion.

When locating an organ with respect to another, or locating a limb, it is necessary to determine a point of reference as to the proximity or remoteness of that point, then in this way it will be easier to determine the position in relation to some structure, in such a way Soriano, P and Belloch Llana, S. (2015), propose the following descriptions:

- CRANIAL OR CEPHALIZE: A structure is cranial, when it is closer to the head (what is superior). For example: the heart is superior to the liver (5).

- CAUDAL: This is when the structure is closer to the tail (which is lower). For example: the stomach is inferior to the lungs (5).

- PROXIMAL: structure that is located closer to the root of the limb. For example: the humerus is proximal to the radius (5).

- DISTAL: structure that islocated farther away from the root of the limb. For example: the phalanges are distal to the carpus (5).

- VENTRAL: Structure that is located in the anterior part of the body. For example: the sternum is anterior to the heart (5) or the pectoralis is anterior to the ribs (1).

- DORSAL: Structure that lies at the back of the body. For example: the esophagus is posterior to the trachea (5) or the thoracic organs are posterior to the ribs (1).

- INTERNAL OR MEDIAL: Point at which it is closest to the midline of the body, and in relation to an organ, it is on the inside. For example: the ulna is medial to the radius (5) or the rhomboid muscle is medial or internally with respect to the scapula (1).

- EXTERNAL OR LATERAL: That which is farther from the midline of the body, as far as an organ is concerned, lies closer to the surface. For example: The lungs are lateral to the heart (5).

- SUPERFICIAL: That which is closest to the surface of the body. For example: the ribs are superficial to the lungs (5) or the skin is superficial to the muscles (1).

- INTERMEDIATE: Between two structures (5).

- DEEP: Structure farthest from the surface of the body. For example: the ribs are deep in relation to the skin of the back and chest (5).

- HIPSOLATERAL OR HOMOLATERAL: structures located in the same part of the body.

- CONTRALATERAL OR HETEROLATERAL: structures located in different parts of the body.

- INFEROMEDIAL: closer to the feet, and to the medial plane (1).

- SUPEROLATERAL: closer to the head and away from the median plane.

.

Planes of motion

As previously mentioned, the movements or sporting gestures are given in the conjugation of the planes and axes of movement, with which some movements will only intervene to a greater or lesser extent in each of them, for that in this section each plane and each axis will be explained in relation to each movement or sporting gesture that characterizes it.

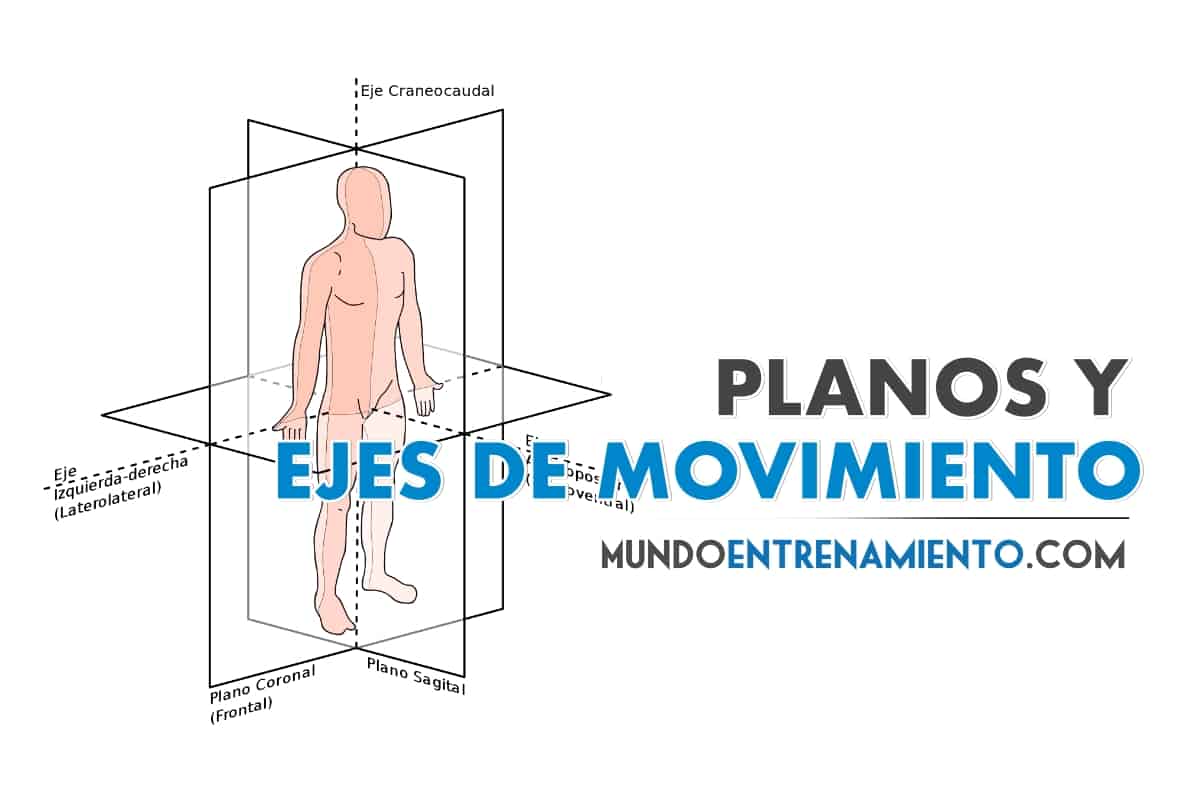

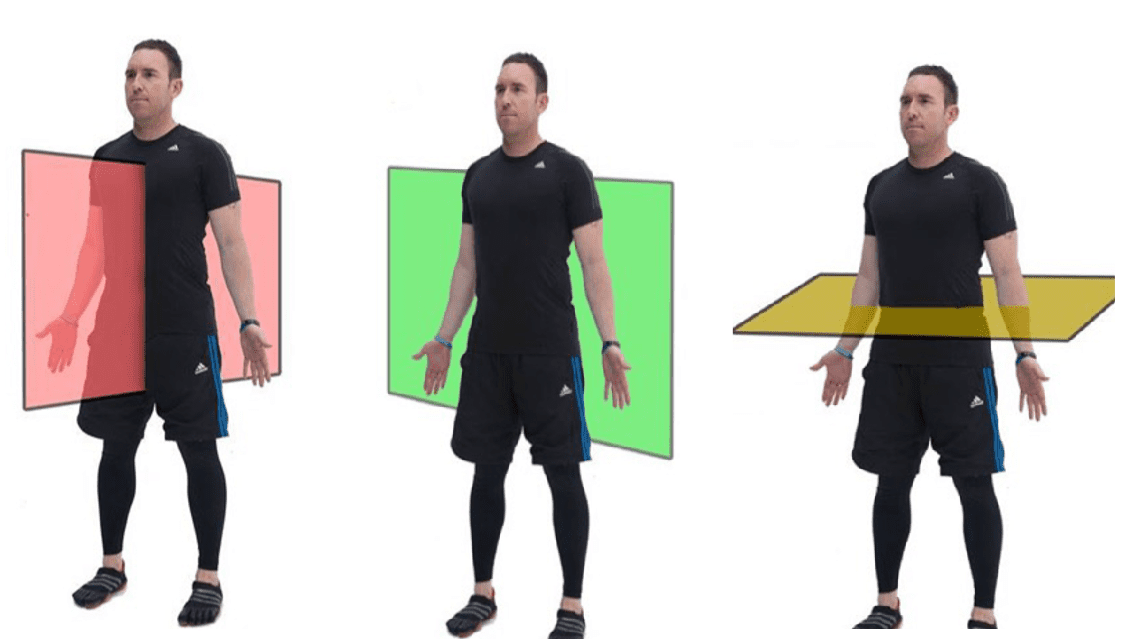

The planes divide the body into two hemispheres, which derive from 3 dimensions of space, forming right angles between them by their arrangement (6).

For this, we distinguish three planes, the Sagittal, Frontal and Transversal and their axes are; Transversal, Anteroposterior and Vertical or perpendicular.

In contrast, the study of the body regions, are performed by means of cuts or sections, in which it is understood that it is a flat surface of a three-dimensional structure or a cut along one of the 3 planes (5).

Sagittal or Anteroposterior Plane

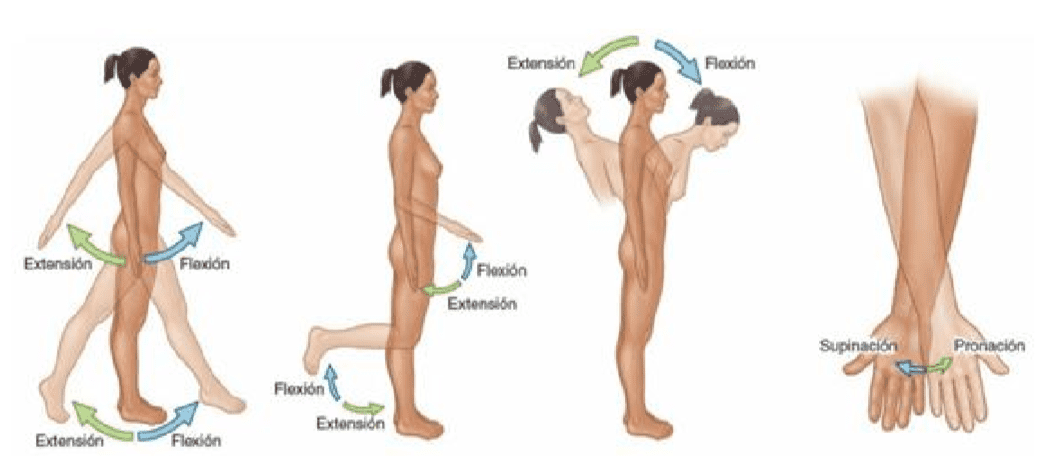

This plane divides the body into two hemispheres, right and left, as it extends from front to back. The movements carried out in this plane are flexion and extension. In addition, this plane corresponds to the Transverse Axis (6).

For Calais-Germanin, B., (1999), the forward movement of the anatomical position is called flexion, and backward extension.

But in relation to the shoulder and ankle joint, they will be called: for the shoulder(antepulsion: forward movement) and the backward movement retropulsion.

However, in the ankle, dorsal flexion is the forward movement and plantar flexion is the reverse (2).

Furthermore, if this plane does not pass through the midline of the body, and divides the body into two unequal halves, it is known as the Parasagittal Plane (5).

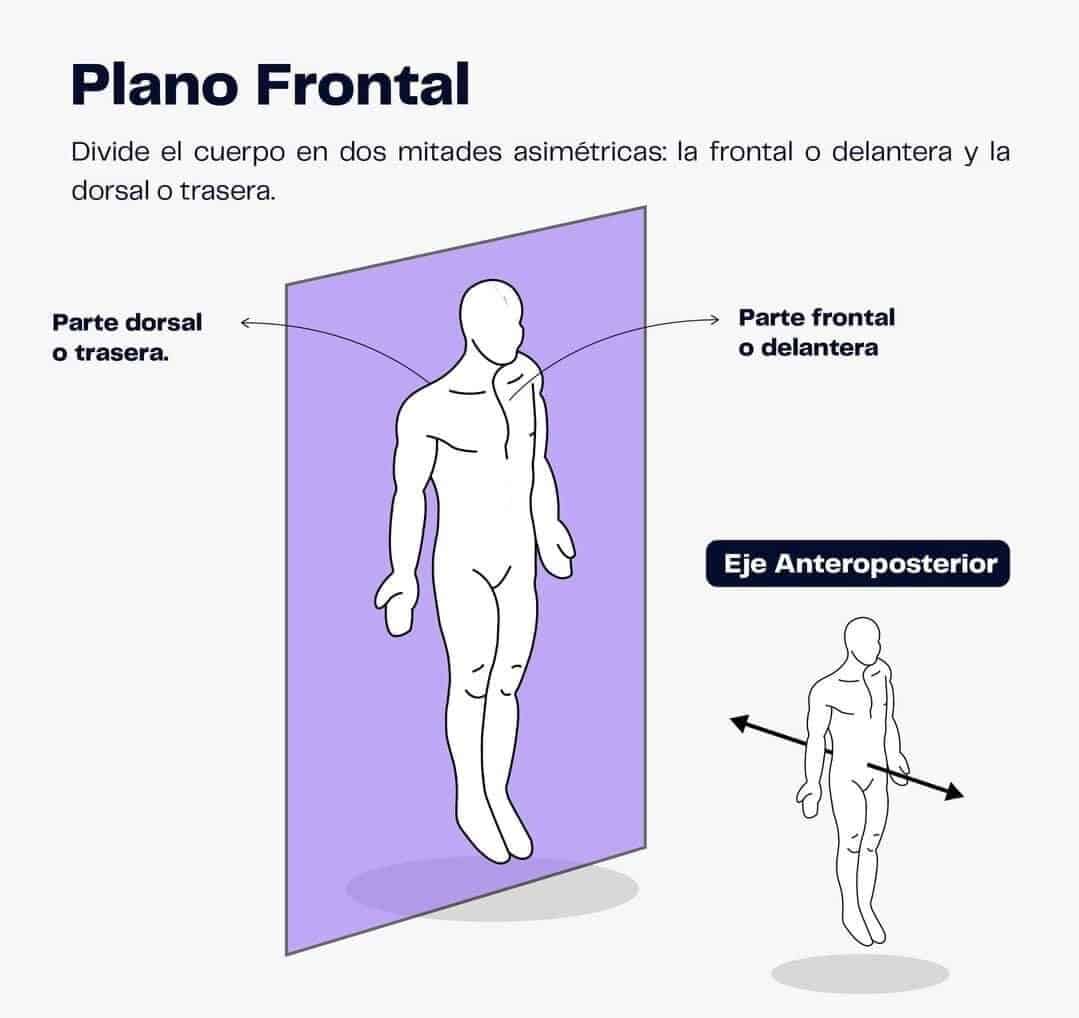

Frontal or Coronal Plane

This plane divides the body into two hemispheres, anterior and posterior, and the movements carried out are Abduction (separation) and Adduction (movement towards the body line). For this Plane, the Anteroposterior Axis (6) corresponds.

On the other hand, for the movements of the trunk, they will be called lateral tilt, when it moves away from the midline (2).

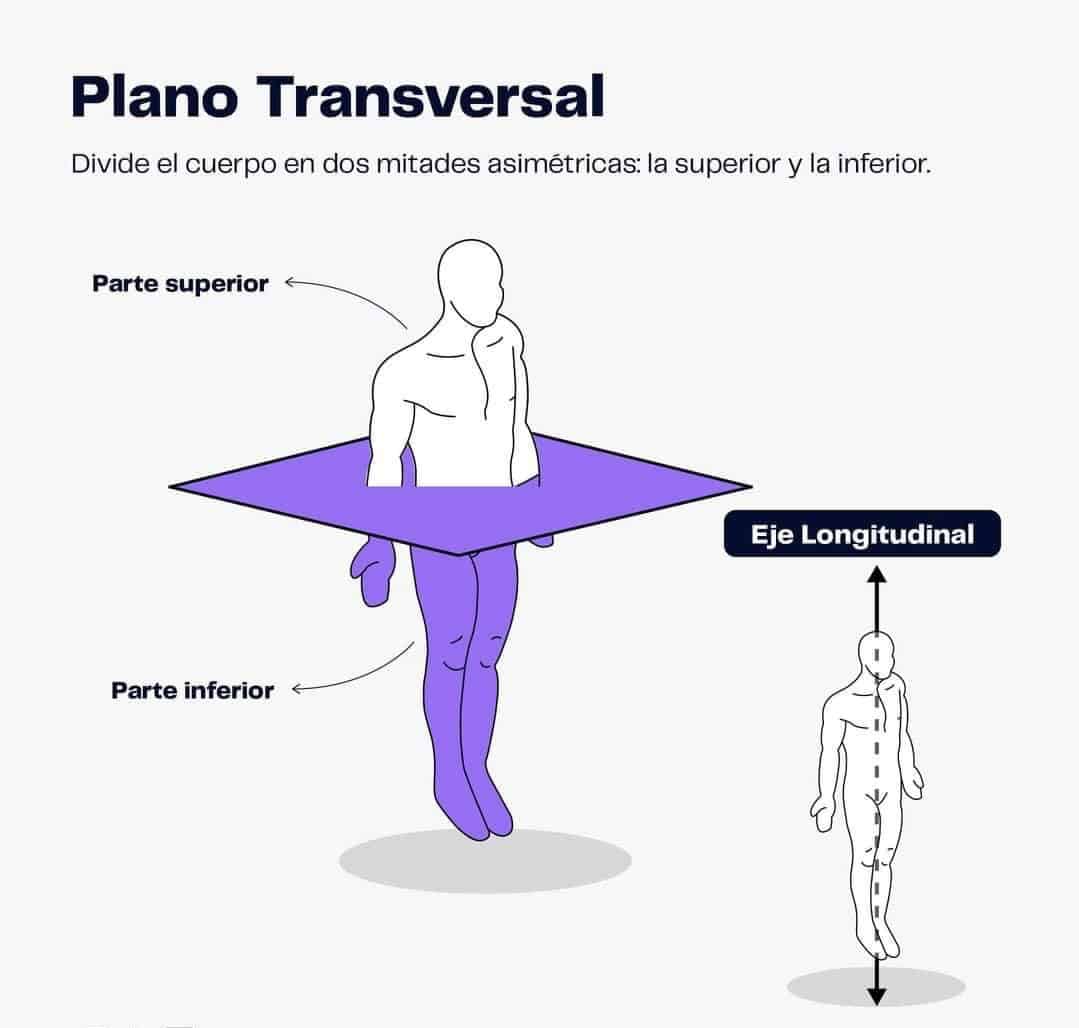

Transversal or Horizontal Plane

This plane divides the body into two upper and lower hemispheres, and on this plane the movements of external and internal rotation and to the right and left are made through the vertical or perpendicular axis (6).

However, Calais-Germanin, B., (1999) , mention that the movements that are performed outward, belong to the external rotation, and inward, to the internal rotation, and as for the trunk, the rotations are to the right or left, and in the forearm, pronation corresponds to internal rotation and supination to external rotation.

Finally, another plane to take into account is the Oblique Plane, which, in contrast, will cross an organ or the body at an angle between the transverse and sagittal plane or between the transverse or frontal plane (5).

Axes of motion

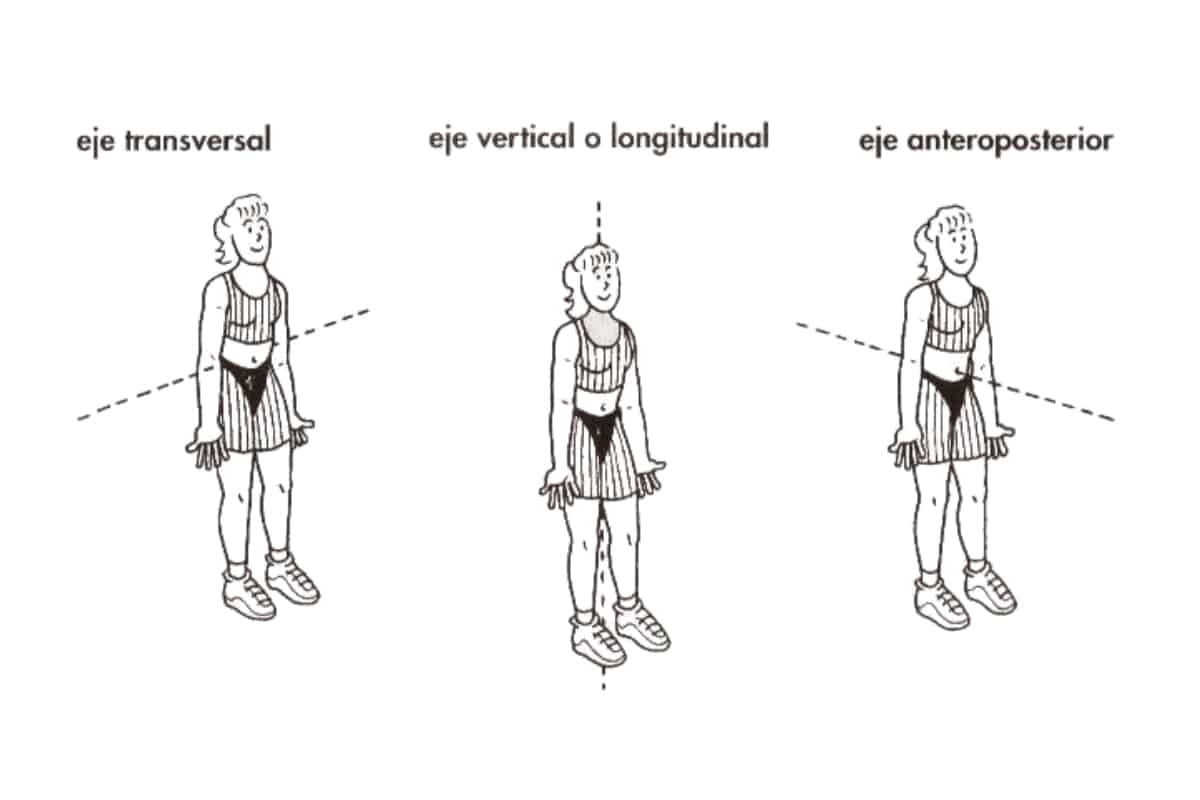

Regarding the body axes, it is known from the vertex of the head, which passes through the sixth cervical vertebra, through the first lumbar, through the center of gravity located in the pelvis, and goes towards the feet in a straight line, this line is an imaginary line along which the movement takes place (6).

It also comes from the Greek axis, in which Estrada Bonilla, Y (2018), define it as a line that crosses the body in various ways, and where a reference is established for the various movements.

On the other hand, the union of two or more axes, form a plane (Estrada Bonilla, Y. 2018), which as mentioned above, would form the reference system in which allows to observe and describe the movement in its three body axes, the Frontal or latero-lateral Axis, the Longitudinal or vertical Axis and the horizontal or antero-posterior Sagittal Axis.

Horizontal or latero-lateral frontal axis

You must choose a joint as a reference point to achieve traverse the body (4).

Longitudinal or vertical axis

Crossing the body from top to bottom (4).

Horizontal or antero-posterior sagittal axis

This axis crosses the body from front to back (4).

.

Movements for planes and axes of motion.

The movements, which occur in the mentioned planes and axes of movement, and who carry them out are the joints, these rotational movements, occur in the upper and lower part of the body (7).

In this section, we will observe the different movements that exist, in relation to the planes and axes of movement, as proposed by Estrada Bonilla, Y. (2018).

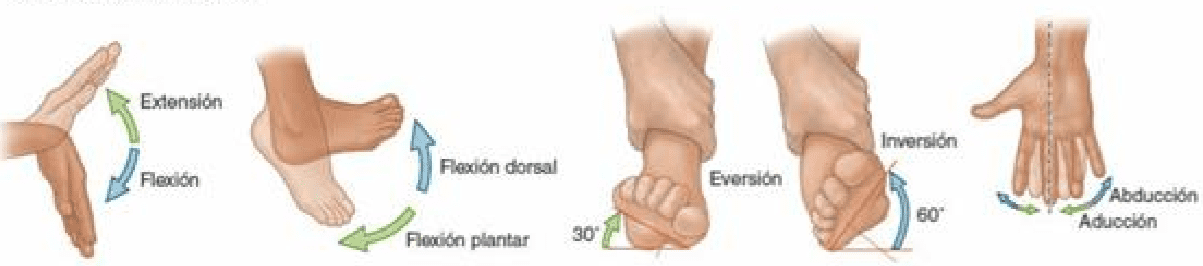

- FLEXION: Movement of approximation between two bones, together with the action of the joint and muscles.

- EXTENSION: It is a movement that opposes flexion, with which the two bones move away.

- PRONATION: A rotational movement of the forearm, in which the hand is positioned with the back of the hand facing upwards.

- SUPINATION: movement opposite to the previous one, where the palm of the hand is positioned upwards.

.

- ABDUCTION: A body segment moves away from the midline of the body.

- ADDUCTION: Movement opposite to abduction, where the body segments move closer to the midline of the body.

- EVERSION: movement of the ankle, in which there is a lateral displacement, the toe points to the side.

- INVERSION: movement of the ankle towards the medial side.

.

- EXTERNAL ROTATION: It occurs when a segment or joint rotates to the side.

- INTERNAL ROTATION: The segment or joint rotates medially.

- AXIAL ROTATION: The segment or joint that rotates about its own vertical or longitudinal axis.

- LATERAL FLEXION: movement in which it tilts to the right or left. For example, the trunk and neck.

- CIRCUNDUCTION: a combination of flexion, extension, abduction and rotation. It is a wide circular movement, for example in the shoulder joint (1).

- SLIDE: performed on flat surfaces (1).

- OPPOSITION: when the thumb contacts the little finger across the midline of the hand (1).

- REPOSITION: the opposite movement to the previous one (1).

.

In this way, it is determined the importance of the knowledge of the planes and axes of movement so that in this way we can analyze and observe the sport gestures or movements, both to prescribe training and to strengthen weakened movement patterns.

Conclusions on the planes and axes of motion

When performing any movement or biomechanical analysis, the basis of it is to define the position that the body has at the time of being studied, for this reason using tools such as observation and analysis, in relation to the planes and axes of movement, the line of gravity and center of gravity, will give us a clearer picture to better understand the biomechanical patterns of movement of the structures studied.

In addition, there is a correspondence of that for each of the planes and axes of motion and this will allow us to determine a frame of reference in relation to the joints involved in each movement.

That said, understanding the planes and axes of motion will allow us to optimize training, depending on the objective, whether it is muscle mass gains, strength gains, recovery from injury, or strengthening of weakened movement patterns.

Bibliographic references

- Agur, A. F. (2019). Moore’s Essential Clinical Anatomy, 6th edition. Barcelona(Spain) : Wélters Kluwer.

- Calais-Germanin, B. (1999). Anatomy for movement. Introduction to the analysis of body techniques. Madrid: La liebre de marzo.

- Drake, R. L., Wayne, V., and Mitchell, A. W. M. (2005). Gray anatomy for students. Madrid: Elseiver.

- Estrada Bonilla, Y. (2018). Biomechanics: from mechanical physics to the analysis of sport gestures. Universidad Santo Tomás. Faculty of Physical Culture and Sport and Recreation. USTA Editions.

- Tortora, G and Derrickson, B. (2010). Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. Planes and axes of motion. 11th edition. Editorial Médica Panamericana.

- Soriano, P and Belloch Llana, S. (2015). Basic biomechanics applied to physical activity and sport. University of Valencia. Editorial Paidotribo.

- Zarate Rodriguez, et al. (2018). Sport science policy guidelines. Biomechanics. Bogotá, D.C. Colombia. Coldeportes.