In this article, we will analyze fine and gross motor skills in boys and girls. Before delving into these two terms of fine and gross motor skills, we need to know that physical activity, and with it Physical Education, is fundamental for the early development of each child and greatly affects the health aspects of the young person (1).

The WHO suggests that higher levels of physical activity in school-aged children are associated with significant short- and long-term health benefits in physical, emotional, social, and cognitive domains throughout life (2, 3).

Therefore, it is essential to integrate physical activity into children’s lives and establish foundations to facilitate learning and also maintain a healthy and active lifestyle during adulthood.

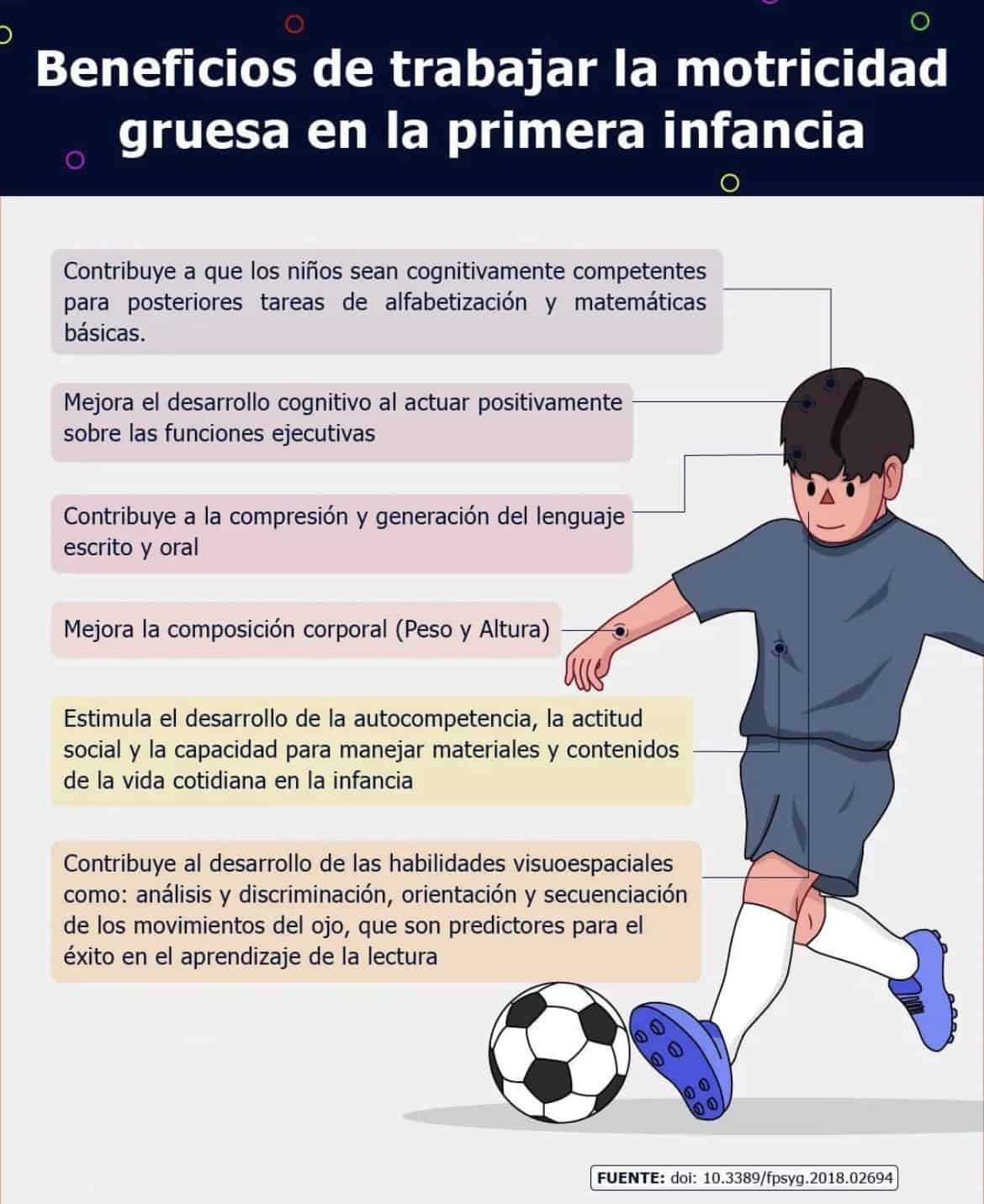

Promoting physical activity, psychomotricity, and fine and gross motor skills in early childhood helps develop motor skills and also improves academic performance (4).

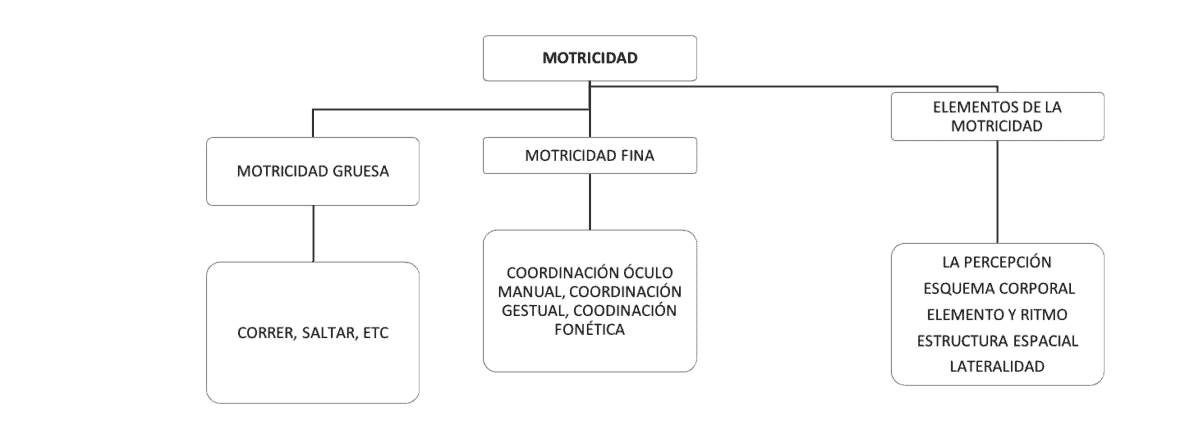

Types of motor skills: fine and gross motor skills

Fine and gross motor skills refer to the control that humans are capable of exerting over their own bodies.

Motor skills are a capacity related to the development of specific movements and gestures. In the case of gross motor skills, it refers to all those more complex and global motor movements such as running, jumping, walking, turning, throwing objects, etc.

Fine motor skills, on the other hand, refer to all those activities that require eye-hand coordination and the coordination of specific muscles (cutting shapes with scissors, holding a pencil to draw, etc).

The development of this psychomotricity and fine and gross motor skills is essential for the acquisition of skills, therefore, it is important to stimulate this development in the early stages of education.

Neuroscience and fine and gross motor skills

Today, advances in neuroscience have generated substantial progress in connecting exercise with brain structure and cognitive development (5).

Physical activity has a positive effect on cognitive functions, partly due to physiological changes in the body.

For example, the increase in levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) can facilitate learning and maintain cognitive functions by improving synaptic plasticity and serving as a neuroprotective agent, leading to better neuroelectric activity and increased cerebral circulation (6).

Psychomotricity in education: fine and gross motor skills

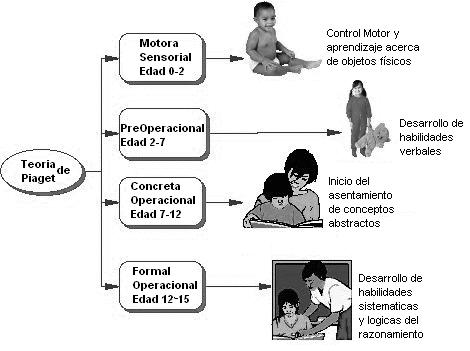

Psychomotricity plays a very relevant role in the early childhood education stage, as it is demonstrated that in early childhood there is a great interdependence in motor, affective, and intellectual development.

Piaget’s theory even states that the child’s intelligence is built from the motor activity they perform. Therefore, in the early years of a child’s education, up to approximately 6-7 years of age, education is psychomotor because all knowledge and learning stem from the child’s own action on the environment and experiences.

Fine and gross motor skills are the domain that humans are capable of exerting over their own bodies. It is something integral as all systems of the organism are involved.

These motor skills manifest all human movements. These movements determine the motor behavior of children from 0 to 6 years through basic motor skills (7).

Gross motor skills

The acquisition of gross skills is conceived as a systemic process, where visual perception and movement execution influence each other reciprocally.

Gross motor skills involve large body movements, of a more global nature, such as jumping, running, and walking. These movements improve progressively throughout the Early Childhood Education Stage.

Stage from 0 to 6 months

In this stage, there is complete dependence on reflex activity, especially sucking. By around 4 months, voluntary movements begin due to external stimuli.

6 months to 1 year of life

It is characterized by the organization of new movement possibilities. Greater mobility can be noted, which integrates with the development of space and time. It is closely linked with muscle tone and the specific maturation of the growth process.

1 to 2 years of life

Around one year of life, the child can walk autonomously and can climb steps with some help. By the age of 2, they can run and jump with both feet together. Additionally, they squat, and new specificities in movement appear.

3 to 4 years of life

In this stage, what has been acquired until then is consolidated. Certain basic motor skills like running are consolidated, and they already experience new experiences like tiptoeing, climbing stairs without help or support, etc.

5 to 7 years of age

Balance appears in a very important phase, at this age, total autonomy is acquired. The knowledge acquired up to this point is automated and perfected.

From 7 years onwards

It is from 7 and 8 years of age when maturation is completed, therefore, from this moment and until the end of Primary Education (12 years), it is the most appropriate time to carry out activities that promote balance and coordination of movements.

According to the educator Carlos Plana, it is at these ages where basic motor skills should be promoted, and once these are consolidated, they should be perfected with pre-sport activities.

Fine motor skills

The control of these motor skills refers to the coordination of neurological, skeletal, and muscular functions.

It constitutes a more specific refinement of the control of gross movements and therefore, its development and expression take longer. Moreover, the control of these fine motor skills is one of the elements used to determine the developmental age of a child.

Fine motor skills involve precision, efficiency, and harmony. They can also be defined as all those human actions in which eye-hand intervention is involved, as previously anticipated. Although eye-foot interaction is also included (7).

0 to 12 months

They do not have eye-hand control, but towards the end of the first year of life, certain beginnings of control over their hands appear (touching the palm, closing the fist, etc).

This last movement refers to an unconscious reflex called the “Darwinian reflex” and disappears at 3-4 months. Therefore, at this moment, they can grasp an object placed in their hand but without any voluntary knowledge.

Eye-hand coordination begins to develop from 3-4 months, starting a new period called trial and error, seeing objects and trying to grab them. Finally, around the fifth month, they manage to grab an object within their reach.

The most relevant fine motor skill achievement of this stage appears from 12 months, known as picking up things using fingers like pincers (pinching).

1 to 3 years of age

The child’s own curiosity and development make them dare to manipulate objects in an increasingly complex way.

The drawings they execute are scribbles, but they begin to make more or less circular figures that will serve as a pattern for executing more complex drawings.

3 to 5 years of age

In this stage, they begin to experience an important motor evolutionary leap. They start with greater control of the pencil and draw human figures, animals, and others with simple strokes.

But it is towards the end of this stage when they already have greater eye-hand control. In handling scissors, clay, etc.

5 years of age

From the age of 5, children consolidate and advance significantly beyond the development achieved in the previous stage. They perfect what was previously acquired.

They already cut and paste with criteria and are capable of buttoning small buttons and having greater motor control in routine tasks.

Importance of fine and gross motor skills

As we can see, the development of fine and gross motor skills is closely linked with the enrichment of teaching and learning for children in the academic field.

Therefore, the development of fine and gross motor skills becomes fundamental from the preschool and Early Childhood Education stages, carrying out interdisciplinary work between the tutor of that stage and the professional who teaches psychomotricity in those stages.

Physical Education plays an important role also in early ages, both for the development of fine and gross motor skills and for the establishment of routines and habits that will be reinforced in Primary Education.

Bibliographic references

- King G., Law M., King S., Rosenbaum P., Kertoy M. K., Young N. L. A conceptual model of the factors affecting the recreation and leisure participation of children with disabilities. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2003;23(1):63–90.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2008) Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Washington, wash, USA: US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar].

- National Institutes of Health. Benefits of Physical Activity. 2016, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/phys/benefits.

- Timmons B. W., Leblanc A. G., Carson V., et al. Systematic review of physical activity and health in the early years (aged 0–4 years) Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 2012;37(4):773–792.

- Donnelly J. E., Hillman C. H., Castelli D., et al. (2016). Physical Activity, Fitness, Cognitive Function, and Academic Achievement in Children. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 48(6):1197–1222.

- Hillman C. H., Erickson K. I., Kramer A. F. (2008). Be smart, exercise your heart: exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience.9(1):58–65.

- González, C. (2001). Physical Education in preschool. fine and gross motor skills Cuba: Deportes de cuba.

- Le Boulch, J. (1995) “Psychomotor development from birth to 6 years”. fine and gross motor skills Educational Consequences. Ediciones Paidós, Barcelona.